One of the challenges with studying furniture is compiling a large enough body of work to draw conclusions and make comparisons, so it is little wonder that when a group of interesting, connected objects is identified, academic and financial interest are both often intense. Such is the case with the furniture known as “Soap Hollow.”

One of the challenges with studying furniture is compiling a large enough body of work to draw conclusions and make comparisons, so it is little wonder that when a group of interesting, connected objects is identified, academic and financial interest are both often intense. Such is the case with the furniture known as “Soap Hollow.”

Soap Hollow, a hollow in Somerset County, Pennsylvania, allegedly so named because of the brown soft soap manufactured there, was also home to a group of Mennonite cabinetmakers who worked throughout the 19th century, roughly from 1830 to 1890, with a significant uptick around 1850 in the number of pieces extant. There was a core group of at least eight men who constructed the furniture, using similar forms and configurations, construction and decoration techniques.

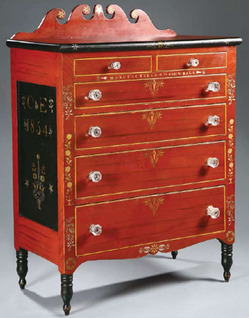

The decoration is what tends to grab the eye, as the majority of Soap Hollow pieces were decorated with vibrant paint and embellished with stenciling, often in dramatic color combinations like dark red and black. Stencils ranged from the more ordinary floral and geometric motifs to rarer (and thus more desirable) eagles, horses, hearts, and bowls or baskets of fruit. There are also stencil patterns that still survive, but with designs that have not yet been found on Soap Hollow pieces. Stenciling was often done in gilt and the initials of the owner and the date were also often stenciled on the pieces. In the last decade or so of production, some of the pieces began to have decoupage-style decoration, often in the form of flowers under layers of clear varnish. A variety of forms, from boxes and cradles to beds and cupboards, are known to have been produced in Soap Hollow, but the most common forms are the blanket chest and the chest of drawers.

Part of what makes Soap Hollow furniture so intriguing to study is that there were other people outside the community making furniture in the same Germanic tradition (particularly in regards to the paint choices and the stenciling), many of whom moved on throughout the Midwest (taking their stencils with them, of course), settling in other heavily Germanic areas throughout Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana, even onto the plains of Kansas. The internet has allowed researchers to make huge inroads with study, identifying other groups of related furniture, conducting and sharing genealogy research, and comparing images to make connections.

With so many objects available, Soap Hollow material has accumulated quite a following in the marketplace. Small pieces such as hanging boxes or sewing caddies can often be had for several hundred dollars, but the most desirable Soap Hollow pieces are those that are classic forms for the region (typically blanket chests and chest of drawers), that are marked with the traditional stenciled maker’s mark, and that have bright, clean paint with exuberant decoration. These pieces routinely bring several thousand dollars and have been known to fetch more than $25,000, with a few outliers bringing several times that amount.

![Redware; Bell (Samuel), Shenandoah Valley, Figures (2), Dogs, Whippets, Recumbent, Paint Decoration, 10 inch. A very rare and important pair of Shenandoah Valley redware [dog figures depicting] whippets, both signed Samuel Bell / Winchester Sept 21 1841, Winchester, Virginia origin, matched pair of molded redware whippet figures with incised details to face and paws, both dogs painted black with white-and-red eyes and red mouths, reclining atop green-painted bases with incised borders.](http://www.prices4antiques.com/item_images/medium/68/38/94-01.jpg)

![Furniture: Chair-Rocking; Campeche, Cherrywood, Half Round Crest, Leather Sling Upholstery, Curule Base. Furniture: A Louisiana carved cherrywood campeche rocking chair, early 19th century, distinctive architectural half-round crest, continuous back and seat with leather [sling] upholstery and nailhead trim, serpentine arms and supports over curule rocker base, pegged and tenoned construction.](http://www.prices4antiques.com/item_images/medium/61/13/68-01.jpg)