![Furniture: Teapoy; William IV, Walnut, Carved & Burled, Octagonal Top, Reeded Vasiform Pedestal, Tripod Legs. An English [William IV] carved and burled walnut teapoy, circa 1840, octagonal hinged top opening to fitted interior with lidded tea compartments, mixing bowl not present, reeded vasiform pedestal, tripod cabriole legs.](http://www.prices4antiques.com/item_images/medium/56/12/76-01.jpg)

While fads have come and gone over the years, many furniture forms have remained the same: nightstands, chests of drawers, wardrobes, but every now and then there is a form so specialized and so linked to the era in which it was used that it is now virtually alien in the modern age. The teapoy is one such form.

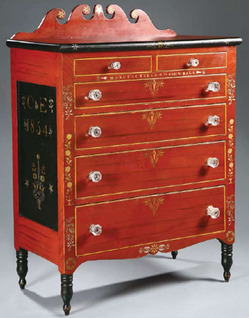

Teapoys came into being in the Georgian era, in the last half of the 1700s, as a tiny portable stand meant to hold an individual cup and saucer, acting almost like the modern folding tray or TV table. With a small circular or octagonal top on a central column with three feet, the table is thought to have drawn its name from “ti-n,” the Hindu word for three, and “pae,” the Persian word for foot, with “ti-n” quickly being transformed into “tea” because tea was what the form was used exclusively for. (The name is now commonly teapoy, but tepoy was also used historically.) Early versions were rather basic and plain in materials, but walnut, satinwood, and, of course, mahogany soon became the woods of choice. The style of the form also evolved, with both the legs and the column slimming down, but the top was traditionally octagonal.

After the Revolutionary War as the economy settled down, tea prices began to drop and tea became much more popular and widely available. In a short period of time, the modest boxes and cannisters that had held tea were too small for the volume of tea being purchased and tea caddies became popular. Tea was still considered precious though and kept under lock and key, because not only could it be stolen but it could also be “diluted” with “smouch,” a term that meant any filler or additives added to tea by crooked merchants – not unlike the way a modern drug dealer might stretch a product with the addition of baking soda or other household powders. Smouch, typically dried leaves from various trees, was most readily detected when added to unblended teas, so unblended tea became costly and, of course, a status symbol. The lady of the house would blend tea in front of the guests, thereby assuring them of the quality of the tea they would be consuming and thereby requiring bigger and bigger tea caddies, which were too bulky to carry in with the tea things on a tray.

Thus, enter the teapoy, which offered a fashionable, efficient way to keep the tea caddy close at hand for blending tea. But because the first teapoys were small stands with no applied, raised trim around the edges, tea caddies were perched on them rather precariously. By 1810, tea caddies and teapoys had united in one form, a true Regency teapoy, a small, elegant, readily portable piece of furniture, a tea caddy on a baluster/pillar base, that could remain at hand at all times. They were only in the finest homes and they would evolve in every possible direction of ornamentation – different shapes, veneers, expensive woods, painted scenes on the interior lids, ormolu mounts and more. (The one pictured above, from the William IV era, shows how they would change.)

Since this time, teapoy has begun to be misapplied to other forms, particularly candlestands and small side tables, sometimes even sewing stands. True early teapoys had octagonal tops, with only a few known circular exceptions. They also lacked the raised rim found on many tables of comparable size. Later teapoys are more easily identified by their compartments, obviously intended for tea. Today, their values can vary widely. Some of the more decorative examples have sarcophagus tops or other stepped designs that make them unsuitable for use as side tables, thus affecting their functionality and collectability, but fine examples can still fetch several thousand dollars.

![Furniture: Wardrobe; Schrank, Zoar, Cherry & Walnut, Molded Cornice, 1 Paneled Door, Canted Corners, Diamond Panels. Furniture: A carved schrank, Zoar, Tuscarawas County, Ohio, mid 19th century, cherry, walnut, and poplar. One-piece [wardrobe],with [molded cornice], canted and carved pilasters, paneled door, and diamond panels below the door. Interior with carved hooks and a shelf.](http://www.prices4antiques.com/item_images/medium/61/28/04-01.jpg)