In the late 14th century, Jan Hus, a Roman Catholic priest in Prague who had been heavily influenced by reformer John Wycliffe, began to attract followers as he spoke out about indulgences (a key practice Martin Luther would attack again in 1517) and his belief that church members should be able, permitted, and encouraged to study the Bible themselves. Hus’s continual agitation would put him at odds with the Catholic Church and in 1415 he would be burned at the stake as a heretic.

In the late 14th century, Jan Hus, a Roman Catholic priest in Prague who had been heavily influenced by reformer John Wycliffe, began to attract followers as he spoke out about indulgences (a key practice Martin Luther would attack again in 1517) and his belief that church members should be able, permitted, and encouraged to study the Bible themselves. Hus’s continual agitation would put him at odds with the Catholic Church and in 1415 he would be burned at the stake as a heretic.

Despite this gruesome attempt at silencing them, Hus’s followers were undeterred and remained firm in their conviction that reformation was needed. It would take more than 40 years, but in 1457, they would formally organize themselves as the Unitas Fratrum (United Brethren), simultaneously establishing themselves as one of the first Protestant religions. The political and religious situation in the region was regularly changing, permitting the German-speaking members to worship freely at times and subjecting them to persecution at others, but by the Reformation in 1517, the United Brethren would number 200,000 members with more than 400 houses of worship.

Within a century, turmoil would again make life in the region difficult for the United Brethren, who found themselves suffering from heightened intolerance, driven in part by the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), which would conclude with Catholicism becoming the official religion of the region, forcing the remaining members to flee or worship secretly.

The following years were lean ones for the Brethren, who were in fact nearing extinction by the 18th century, until Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf offered them sanctuary on his Saxony estate, an offer he had extended to many persecuted Protestant groups who found themselves under siege. The various groups would collaborate on the construction of Herrnhut, a settlement where all were allowed religious freedom.

The Moravians, as the group had become known by the name of their native region, found favor with Zinzendorf, who felt they would make excellent missionaries with his support. In the mid-18th century, they would travel through Northern Europe, the British Isles, and even into Greenland, spreading their religious beliefs. After a time however, outside political pressure on Zinzendorf lead to renewed persecution and some of the Moravians felt that true religious liberty could only be found in the New World.

After a failed start in Georgia, the Moravians moved to Pennsylvania in 1741, purchasing land north of Philadelphia where, again with help from Zinzendorf, they built the Bethlehem commune. Over the next decade the society’s numbers would grow from approximately 20 members to several hundred. From this point of settlement, a community that would become the locus for the Moravians’ missionary efforts in North America, they would go on to develop 32 missions. Perhaps the next best-known settlement is that of Bethabara, which would become the Salem in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, the first of a number of settlements on a huge tract purchased in the Carolinas. The Moravian Church is still in existence today, although the communal nature of their lives, never as tightly restricted as some of the separatist communities by nature of their zeal for evangelism, faded away within just a generation or two.

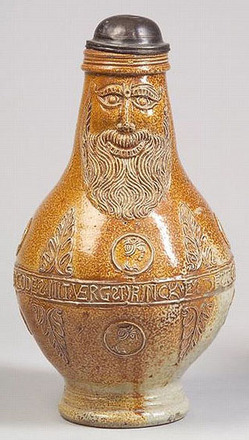

The communities would operate like many other communes, producing and manufacturing to meet the needs of the immediate community and then cultivating clients in the outside world and using the income to support their missionary work. The Moravians lent their name to a rustic chair that is a fairly standard European “peasant” chair and other furniture linked to them and bearing heavy Germanic influences occasionally appears, but they are by far best known for their pottery, particularly their exuberantly decorated redware and their figural flasks, which can fetch thousands of dollars at auction.

![Redware; Bell (Samuel), Shenandoah Valley, Figures (2), Dogs, Whippets, Recumbent, Paint Decoration, 10 inch. A very rare and important pair of Shenandoah Valley redware [dog figures depicting] whippets, both signed Samuel Bell / Winchester Sept 21 1841, Winchester, Virginia origin, matched pair of molded redware whippet figures with incised details to face and paws, both dogs painted black with white-and-red eyes and red mouths, reclining atop green-painted bases with incised borders.](http://www.prices4antiques.com/item_images/medium/68/38/94-01.jpg)

Crack open a container of cocoa mix today and what you have would be unrecognizable to centuries’ of hot chocolate lovers. And yes, centuries. Cocoa beans made the trip to Seville, Spain from Mexico in 1585, but that would have been unrecognizable to us, as it was not the cocoa powder we use (stripped of the rich cocoa butter) but something more akin to melting a chocolate bar and thinning it with cream. And then adding things like anise and chiles!

Crack open a container of cocoa mix today and what you have would be unrecognizable to centuries’ of hot chocolate lovers. And yes, centuries. Cocoa beans made the trip to Seville, Spain from Mexico in 1585, but that would have been unrecognizable to us, as it was not the cocoa powder we use (stripped of the rich cocoa butter) but something more akin to melting a chocolate bar and thinning it with cream. And then adding things like anise and chiles!