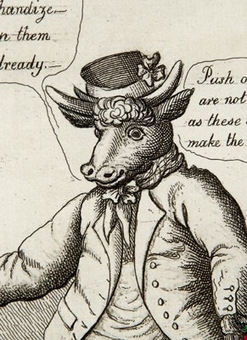

![Stoneware; Anna Pottery, Bottle, Presentation, Railroad Pig, 1882, 8 inch. Salt-glazed railroad engineer presentation pig flask [bottle] by Anna Pottery [Cornwall and Wallace Kirkpatrick, Anna, Illinois], dated 1882](http://www.prices4antiques.com/item_images/medium/59/99/09-01.jpg) Perhaps one of the most iconic Midwestern objects is an Anna Pottery railroad pig flask. Yep, just as strange and quirky as it sounds, and so were many of the things produced by the Kirkpatrick brothers, Cornwall and Wallace, from 1859 to 1896. Both brothers apprenticed to their father, Andrew, a potter, before landing in Anna, Illinois, where they started their pottery. While they’re mostly known today for their unusual objects like their “snake jugs” and the aforementioned pig flasks (one is pictured above), the pottery actually manufactured a great deal of utilitarian wares – crocks, jugs, flowerpots, pipes. As early as 1860, the pottery’s eleven employees produced a total output capable of containing 800,000 gallons!

Perhaps one of the most iconic Midwestern objects is an Anna Pottery railroad pig flask. Yep, just as strange and quirky as it sounds, and so were many of the things produced by the Kirkpatrick brothers, Cornwall and Wallace, from 1859 to 1896. Both brothers apprenticed to their father, Andrew, a potter, before landing in Anna, Illinois, where they started their pottery. While they’re mostly known today for their unusual objects like their “snake jugs” and the aforementioned pig flasks (one is pictured above), the pottery actually manufactured a great deal of utilitarian wares – crocks, jugs, flowerpots, pipes. As early as 1860, the pottery’s eleven employees produced a total output capable of containing 800,000 gallons!A little investigation of the brothers’ history indicates they were just as original. Cornwall became Anna’s first mayor and supported the temperance movement, not necessarily out of any real aversion to alcohol, but because, as a business man, it was more profitable to cater to the prevailing local opinion, which was a conservative one. Meanwhile, Wallace, who ventured to California for a time as part of the Gold Rush, was fascinated with snakes, collecting live ones and displaying them at fairs. The pottery’s snake jugs were, obviously, one of his specialties. Some of the brothers’ pieces are just whimsical, while others carry built-in commentary about temperance, the economy (railroad pig flask), and politics. The story of their pottery captures the very essence of the Midwest: quirky newcomers creating prosperity for themselves in a booming economy driven by agriculture and railroads on a whole new scale!