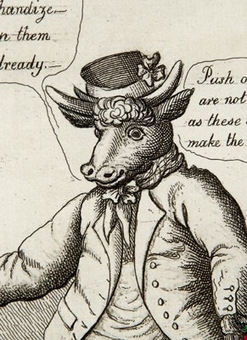

On the Fourth of July, we celebrate our political independence with fireworks and parades, cookouts and pool parties, but our true political independence gets celebrated every day in newspaper op-ed pages where we spout off about whatever’s bothering us and where one can find editorial or political cartoons lampooning every aspect of our political system in a daily, inexpensive, informative celebration of free speech, one of the freedoms we hold most dear. The tradition of lampooning politics in cartoons is a rich one in Britain, and it traveled to America with the colonists. (The detail pictured above is from an etching commenting on the farmers of Alexandria, Virginia buying their way out of occupation during the War of 1812 with rum and tobacco.)

On the Fourth of July, we celebrate our political independence with fireworks and parades, cookouts and pool parties, but our true political independence gets celebrated every day in newspaper op-ed pages where we spout off about whatever’s bothering us and where one can find editorial or political cartoons lampooning every aspect of our political system in a daily, inexpensive, informative celebration of free speech, one of the freedoms we hold most dear. The tradition of lampooning politics in cartoons is a rich one in Britain, and it traveled to America with the colonists. (The detail pictured above is from an etching commenting on the farmers of Alexandria, Virginia buying their way out of occupation during the War of 1812 with rum and tobacco.)

Cartoons might seem silly or pointless decades later, but in reality, they’re very valuable resources to scholars. As the old English proverb goes, many a true word has been spoken in jest, and as is the case with editorial cartoons today, these simple sketches and brief blurbs belie the wealth of information contained about some of the more difficult aspects of history to decipher: what our sense of humor as a culture is like, what we find funny or frustrating or just worthy of comment. They also offer a subtle view of historical events that is sometimes otherwise lost to history. For instance, many people who’ve just taken a history course or two have the sense that the Civil War was popular and that Abraham Lincoln was beloved by everyone north of the Mason-Dixon. In reality, one could tell the entire history of the Civil War, including the political breakdown that preceded it and the frustrating muddle that followed it via editorial cartoons, many of which illustrate a deep disdain or hatred of Lincoln that might surprise people today.

Editorial cartoons were also, in the heightened political climate of the first century of the United States’ existence, a convenient way to convey one’s political viewpoint. A printed, framed copy also offered plenty of opportunity for close scrutiny, something that was necessary with these cartoons that often contain complex symbolism, witty wordplay and intricate illustrations, so Currier & Ives, along with many other engravers and printers of the period, cranked out cartoons with commentary on trade acts, slavery debates, religion, American attitudes toward European conflicts and much more, all intended to be framed and hung in a library, office or study. So the next time you find yourself chuckling or scratching your head after reading an editorial cartoon, remember that you’re participating in a long, rich history of questioning your government!