History is certainly filled with magnificent events: the Emancipation Proclamation, the passage of the 19th Amendment, the discovery of penicillin, the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, and on and on and on. We draw upon all this when we want to be inspired, but history is also ugly, small, and mean and all too often, we draw only upon the parts which allow us to feel good about ourselves. That’s one of the things I love about the database, actually: the balanced picture can’t be erased. We can erase the stories, but we can’t erase the evidence.

History is certainly filled with magnificent events: the Emancipation Proclamation, the passage of the 19th Amendment, the discovery of penicillin, the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, and on and on and on. We draw upon all this when we want to be inspired, but history is also ugly, small, and mean and all too often, we draw only upon the parts which allow us to feel good about ourselves. That’s one of the things I love about the database, actually: the balanced picture can’t be erased. We can erase the stories, but we can’t erase the evidence.

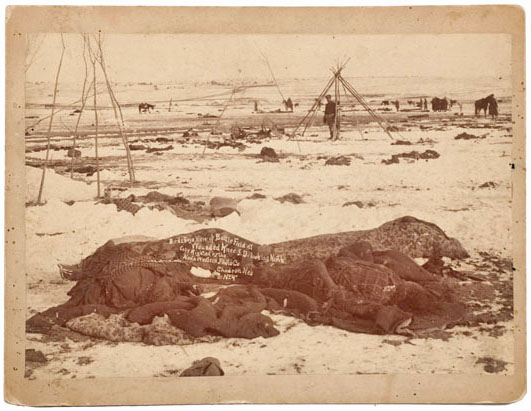

While you might not learn about the events in history classes today, a search of the database will still retrieve beaded pouches designed to carry an American Indian’s ration tickets. Forever woven into the history of many pieces of silver and art are stories of bribes for shelter and aid in fleeing the Nazis. There are Civil War documents with blood stains and bullet holes and we can’t scrub our history of Charleston slave tags or real photo postcards of lynchings. You can find photographs of the dead at Gettysburg, Wounded Knee (see above), Little Bighorn, and on and on. There is an indelible record of the awful things we have done to each other and the planet: engravings of the Boston Massacre, written accounts of life in Confederate prisons, pictures of hillsides obliterated by clear-cutting and objets d’art from the horns and bones and fur of creatures nearing extinction.

That is what makes the field of material culture so interesting and important: words lie. The founding fathers were conscious of the records they left, the boys writing home from all the fronts in all the wars were trying not to scare their wives and mothers, the writings in newspapers were opinions and hyperbole just as they are today. But objects, well, objects are…objective, and by studying them, we can reach different kinds of truth about the past.

No comments

Comments feed for this article

Trackback link: https://www.prices4antiques.com/blog/object-lessons-material-culture-and-history/trackback/