Rare Shaker child's sewing desk, Canterbury, New Hampshire

Typically, when one thinks of the artifacts of a religious group, one thinks of icons, crucifixes, ceremonial silver, not rocking chairs. Yet the Shakers, more accurately known as the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, a group that never had more than about 6,000 full members, have made some of the greatest contributions to American material culture and design.

The Shaker religion appeared in England in 1747, and really began to gain momentum in 1758 when Ann Lee joined them. (Among the many things that reveal Shakers were ahead of their time is their democratic attitude toward women and leadership.) Their basic tenets involved, among other things, a renouncing of worldly goods, a communal life of celibacy and simplicity, and the enthusiastic style of worship that earned them their nickname. The religion’s heyday was over the next century or so; children were adopted by the communities, but the communal and egalitarian nature of the Shaker life no doubt also appealed to women who were disenfranchised, either through abusive marriages or the societal and financial limitations of widowhood.

Today, aside from that quirky idea about celibacy, Shakers are most remembered for the products of their industrious simplicity. Not only did they invent or pioneer a number of ideas – from the “flat” household broom (versus the less effective round version) to packaging and selling seeds in paper packets, but they also created one of the most appealing design aesthetics through their devotion to neat, clean, symmetrical work. Coming to prominence during the Federal period of style, they took what was already a very refined and balanced sense of design and just stripped it down to the most elegant elements.

These days, however, elegant simplicity is probably going to cost you. Shaker pieces are highly desirable (assuming that objects are convincingly Shaker and not just in the “Shaker style”), in part just because of the careful attention to the details of quality construction and in part perhaps because with so few communities, pieces can be more readily identified and researched than other pieces of the same period. In terms of collecting, things fall out fairly simply in terms of price: you have the small things like chairs and pantry boxes that were made in vast quantities for sale outside the communities and you have case pieces, tables, and more specialized forms that were manufactured for use within the community. Chairs, spinning wheels and the like can easily be had for a few hundred dollars, but if it’s Shaker-made AND Shaker-used someone is after, the case pieces (like the one pictured above) generally bring well into five figures. But, after all, simplicity never goes out of style!

-Hollie Davis, Senior Editor, p4A.com.

Reference & Further Recommended Reading:

To search the Prices4Antiques antiques reference database for valuation information on hundreds of thousands of antiques and fine art visit our homepage www.prices4antiques.com

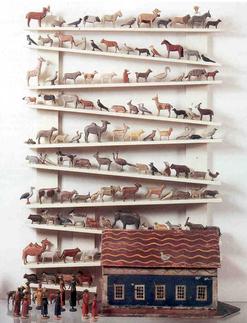

Just about any day now the fall rains are going to start. Of course, it’s only going to seem like it’s rained forty days and forty nights, but when I’m lying awake at night wondering how much more water the septic system can withstand, I can think about Noah and his orderly pairs of animals. Which usually makes my thoughts wonder off, because have you ever noticed that all the depictions include exotic animals and farmyard critters, but no cats? That’s because Noah was probably unable to get the cooperation of cats, if any of his cats were like mine….

Just about any day now the fall rains are going to start. Of course, it’s only going to seem like it’s rained forty days and forty nights, but when I’m lying awake at night wondering how much more water the septic system can withstand, I can think about Noah and his orderly pairs of animals. Which usually makes my thoughts wonder off, because have you ever noticed that all the depictions include exotic animals and farmyard critters, but no cats? That’s because Noah was probably unable to get the cooperation of cats, if any of his cats were like mine….