Timothy O’Sullivan immigrated to New York City from Ireland with his parents when he was a small child and it was there that he later found work in Mathew Brady’s photography studio. (Brady, who was afflicted with vision problems that struck when he was still a young man, depended heavily on the talent he found in recruits like O’Sullivan and Alexander Gardner.) While O’Sullivan appears to have said he was commissioned as a first lieutenant in the Civil War, this does not seem to be confirmed in the records, but he was photographing during the war and by 1862 was certainly working for Mathew Brady as part of Brady’s crew of field photographers.

Timothy O’Sullivan immigrated to New York City from Ireland with his parents when he was a small child and it was there that he later found work in Mathew Brady’s photography studio. (Brady, who was afflicted with vision problems that struck when he was still a young man, depended heavily on the talent he found in recruits like O’Sullivan and Alexander Gardner.) While O’Sullivan appears to have said he was commissioned as a first lieutenant in the Civil War, this does not seem to be confirmed in the records, but he was photographing during the war and by 1862 was certainly working for Mathew Brady as part of Brady’s crew of field photographers.

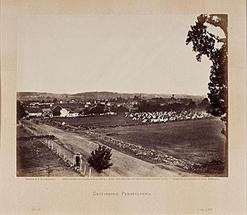

O’Sullivan spent much of 1862 in northern Virginia and would eventually begin working with Alexander Gardner, who had left Brady to work on his own. Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War (1866) would include 44 of O’Sullivan’s photographs, including perhaps his best known image, one of the many he took of the Gettysburg Battlefield, called “The Harvest of Death,” a view of a field somehow chilling in its prosaicism, the idea that it could be any field, anywhere, spread with bodies in all directions as far as the camera’s eye can see. He would also photograph other important events like the sieges of Petersburg and Fort Fisher and Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

While O’Sullivan is perhaps best known for his Civil War work, some of his most magnificent work would be done as an expedition photographer. He traveled with the U.S. Geological Exploration of the 40th Parallel (1867 to 1869), recording the landscape across the frontier. While the official goal was to produce images that would inspire settlers to head west, O’Sullivan also took beautiful images of Native American Indians, their occupations and villages, as well as some of the prehistoric ruins through the Southwest. He would also work with one of the first crews to survey the Panamanian Isthmus for a canal before returning to the American West with the Wheeler Expedition (1871 to 1874). (The trip faced a number of calamities, including the loss of supplies and several boats, which also meant the loss of a number of O’Sullivan’s images.) He would be retained by the U.S. Geological Survey and the Treasury Department as an official photographer upon his return to Washington, but would die in 1882 at just 42 from tuberculosis.

O’Sullivan’s photographs are highly collectible, with, as with all photography, condition and subject matter playing a significant role. Albumen images from the Civil War can bring in excess of $1,000 at auction, while collections of the stereoview photographs taken on the Wheeler Expedition can fetch considerably more.