Lithophane comes from two Greek words: lithos, meaning stone and phainein, which has a more shaded meaning that is close to making something appear quickly. The term refers to an image or scene that is etched or molded into very thin porcelain, so that the intaglio image “pops” when light is placed behind the porcelain. This makes lithophanes three-dimensional, unlike the two-dimensional works of art (prints, photographs, etc.) from which they are often derived.

Lithophane comes from two Greek words: lithos, meaning stone and phainein, which has a more shaded meaning that is close to making something appear quickly. The term refers to an image or scene that is etched or molded into very thin porcelain, so that the intaglio image “pops” when light is placed behind the porcelain. This makes lithophanes three-dimensional, unlike the two-dimensional works of art (prints, photographs, etc.) from which they are often derived.

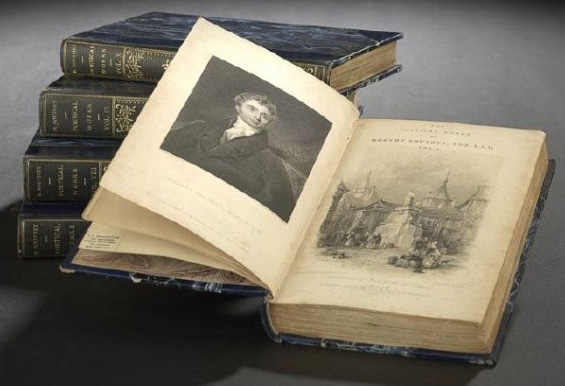

The technique appeared in Europe in the 1820s and spread quickly until they were being made almost everywhere, with the largest porcelain firms like Wedgwood and Belleek cranking them out in enormous numbers. A carver would take warm wax on a sheet of glass and, with the aid of a backlight, carve a scene before handing it off to have a mold cast, which would then be used to create hundreds of castings that were fired. Because of their thinness (as little as one sixteenth of an inch), there was traditionally a fairly high failure rate (some say as high as 60%) for the porcelain castings in the kiln.

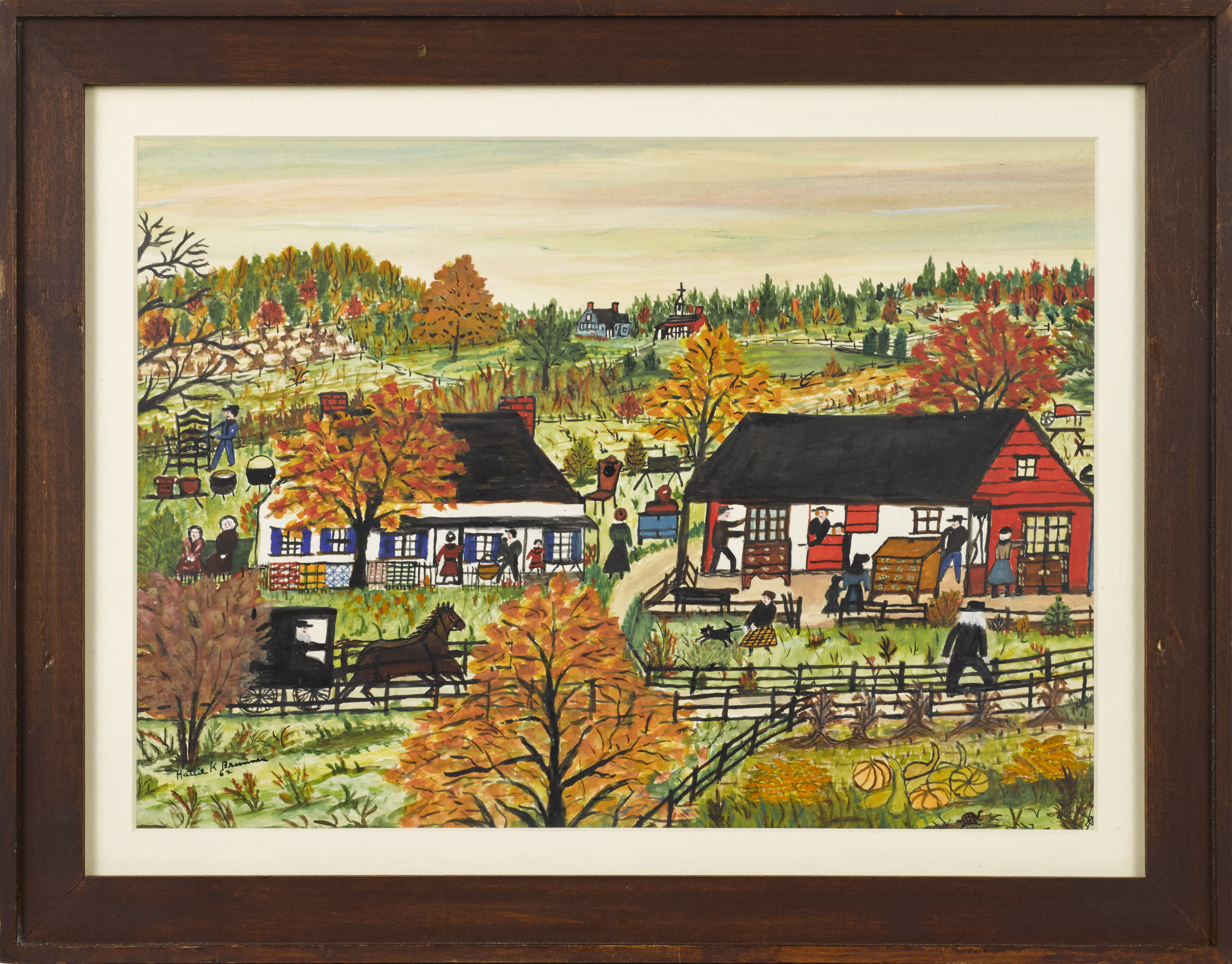

Lithophanes were used, naturally, with objects related to household lighting: night lights, fireplace screens, lamps, but they also were used very cleverly, sometimes for erotic scenes, sometimes in the bottoms of mugs and beer steins, so that as the stein was drained, a scene would appear in the bottom. Lithophanes often depict many of the same scenes that appear in print images: religious events, literary scenes, portraits, etc., with some memorializing historical or political events. They were even used architecturally. For example, Samuel Colt, the firearms magnate, installed dozens of lithophanes throughout his Hartford, Connecticut home.

The value of lithophanes has to do with a number of factors, including the traditional ones regarding condition (or the condition of the object in which they are contained) and the nature/rarity of the object in which they are housed. Steins, particularly the ones with or without lithophanes that are known as regimental steins because they were often given out by military regiments, show this pricing variation clearly. Steins that are just typical steins may only fetch around $100, but ones that have a military history (like the German one pictured here), are associated with rarer military units, have more extravagant decoration, etc., can fetch considerably more. They are also valued based on the scene depicted, with rarer and more unusual views commanding higher prices, and value can also be influenced by the fame of the manufacturer.