Man may have mastered fire millennia ago, but until fairly recently, historically speaking, fire and fire-tending have involved a great deal of equipment and attention. As with many things, we tend to take for granted providing light and heat, illuminating a page, heating up a meal, achieving an accurate temperature to bake bread, but getting a fire started wasn’t always so easy.

Especially after oil lamps and gas lights started to become more common in homes, offering a steady source of a small flame, household mantels began to sport objects known as spill vases. “Spills” were twists of paper, longer than today’s kitchen matches, that were intended to burn long enough to transport flame from lamp to fireplace and to allow the lighter to reach far enough into the fireplace to light a fire. Spill vases, since they were typically intended for a home’s more public rooms and/or were in a position of display on a mantel, are typically very decorative, often some sort of ceramic form with paint decoration. Staffordshire made thousands of them in just about every imaginable form, from courting couples to hunters, whippets to elephants.

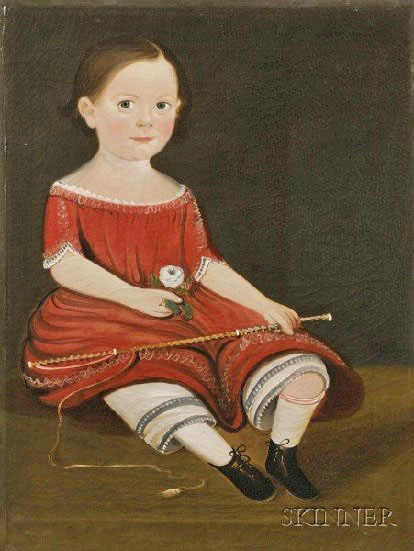

Spill vases should not be confused with match holders, which are smaller containers, often of a later manufacture, although often every bit as decorative as spill vases. Usually manufactured as small, individual or connected double containers, match holders come in a variety of forms, from simple glass containers to figural ones in all sorts of shapes. (This one with a figure of a small boy putting on his socks is particularly cute.) Forms like boots or shoes were popular, but many are in animal or insect form: flies, owls, a donkey hauling baskets. Match holders are also occasionally found with several other small containers meant for use as a smoking set that is designed to hold cigarettes and other tobacco-related paraphernalia. Smoking sets, often manufactured by the same companies that sold desk sets, like this gleaming example from Tiffany, can be elaborate, beautifully decorated objects. Both spill vases and match holders occasionally utilize some natural design in order to create a design with multiple holders, like the terrific Majolica spill vase with frogs and lilypads pictured above.

We’re up to our ears in match holders at the moment, after a recent specialty sale by Whalen Auction of over 550 match holders from a single owner’s collection, so there are certainly many examples in the database. A category/type search in the Prices4Antiques database for “kitchen and household”/”match holders” will show you the most recent examples, including the ones from this incredible sale!

-Hollie Davis, Senior Editor, p4A.com