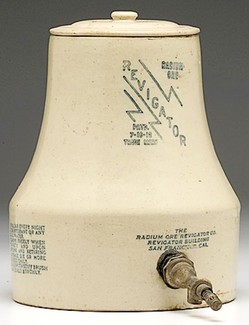

Maybe it’s the contrast with the constant flow of medical news and technological advances, but I’m fascinated recently by all the evidence of “quackery” in the database. Sometimes when one stops to contemplate modern medicine, it’s staggering to realize how dramatically things have changed and in such a relatively short time. Less than 100 years ago, for instance, it wasn’t surprising to encounter containers like the one pictured here. “The Revigator” offered customers a refreshing drink of radon-infused water. Just put a little radium in the inner compartment, fill with water, and let Nature do the work!

Maybe it’s the contrast with the constant flow of medical news and technological advances, but I’m fascinated recently by all the evidence of “quackery” in the database. Sometimes when one stops to contemplate modern medicine, it’s staggering to realize how dramatically things have changed and in such a relatively short time. Less than 100 years ago, for instance, it wasn’t surprising to encounter containers like the one pictured here. “The Revigator” offered customers a refreshing drink of radon-infused water. Just put a little radium in the inner compartment, fill with water, and let Nature do the work!

Quackery actually has a very long history and is likely, I’m sure, to be even older than the word itself, which dates to about 1710 and is based on an old Dutch word, “quacksalver,” meaning “hawker of salve,” salve being one of the earliest forms of quackery. This didn’t change for centuries, as there are any number of salve/ointment containers in the database. (Like this one for Morris Imperial Eye Ointment. If it was a good idea to drink radon water in 1910, I shudder to think of what it might have been thought helpful to put in one’s eye in 1890….) Quackery borrowed the legitimacy of science for marketing purposes, and so it’s no surprised to see every scientific discovery incorporated (or at least claimed to be) for a customer’s benefit. Electricity was, of course, a huge development, and there were dozens and dozens of companies selling machines that promised to use static electricity to cure everything from impotency to rheumatism to the ever-popular “nervous disorders.” When one thinks of how science has advanced in the last century, it’s, well, shocking!

![Hunting; Duck Call, Perdew (Charles), Carved, Flying Mallards. A carved [duck hunting] duck call by Charles Perdew (1874 to 1963) of Henry, Illinois.](http://www.prices4antiques.com/item_images/medium/60/44/61-02.jpg)