Pietra dura (also pietre dure) is an Italian phrase, with pietra meaning “stone” and dura meaning “hard” or “durable.” While pietra dura is the preferred term (at least according to The Getty’s Art and Architecture Thesaurus at http://www.getty.edu/research/conducting_research/vocabularies/aat/), the terms micromosaic or Florentine mosaic are occasionally encountered. (Some find “micromosaic” to be a little objectionable, applying only to the “rougher” forms of the art produced for the tourist trade.)

Pietra dura is derived from the Byzantine art of mosaic work, although mosaics vary slightly in two important ways – grout is typically used in the creation of a mosaic, but more importantly, pietra dura creations are usually portable, while mosaics tend to be larger works, often done on walls or floors. Both are, of course, an art, with pietra dura being referred to as “painting with stone.”

Montelatici pietra dura portrait of a monk. (p4A item # D9807400)

Pietra dura is considered an Italian art, with roots in 14th-century Rome, developing into an art form in Florence, supported by the patrons of the Renaissance and flourishing in the 16th and 17th centuries, and with a later period of popularity in Naples. However, some of the finest works of pietra dura appear in the Taj Mahal in Agra, India, indicating that Indian artisans had perfected the skill by the mid-17th century as well. With the extensive presence of parchin kari, as the art is known in India, in the Taj Mahal, the skill continues to be practiced in Agra, producing lovely, delicate works for the tourist trade.

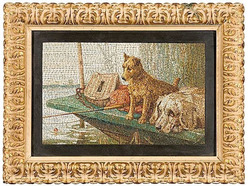

Italian mosaic plaque with two dogs. (p4A item # D9788305)