![Parrish, Maxfield; Oil on Board Landscape Painting, unsigned, The Blue Fountain (Study for Reveries). An oil on board [landscape painting], The Blue Fountain (Study for Reveries), by Maxfield Parrish, American (1870 to 1966), executed circa 1925](http://www.prices4antiques.com/item_images/medium/68/22/12-01.jpg) Frederick Maxfield Parrish was born July 25, 1870 in Philadelphia to Stephen Parrish, an American artist famous for his landscapes, illustrations and engravings and his wife Elizabeth Bancroft Parrish. It’s not surprising that, finding himself surrounded by the tools of his father’s trade, that Frederick (he would begin to use Maxfield as his name later in life) would begin to draw to amuse himself. Around 1881, the Parrish family traveled to Europe, and during the trip, Frederick contracted typhoid. It was during his recuperation that he turned his attention to art in earnest under his father’s tutelage.

Frederick Maxfield Parrish was born July 25, 1870 in Philadelphia to Stephen Parrish, an American artist famous for his landscapes, illustrations and engravings and his wife Elizabeth Bancroft Parrish. It’s not surprising that, finding himself surrounded by the tools of his father’s trade, that Frederick (he would begin to use Maxfield as his name later in life) would begin to draw to amuse himself. Around 1881, the Parrish family traveled to Europe, and during the trip, Frederick contracted typhoid. It was during his recuperation that he turned his attention to art in earnest under his father’s tutelage.

Maxfield studied widely as a young man, abroad in England and France, and at home at Haverford College, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and at the Drexel Institute, where he had the opportunity to work with Howard Pyle, one of the greatest illustrators in American history. While at the Drexel Institute, he also met Lydia Austin, a young instructor, who he would marry in 1895. Parrish himself found work as an illustrator, working in Philadelphia until 1898, by which time his various magazine illustrations for publications and his burgeoning career as the illustrator, especially of children’s books (for authors such as L. Frank Baum and Kenneth Grahame), allowed the young couple to purchase a home, The Oaks, near his parents in New Hampshire.

It was around this time that Parrish developed tuberculosis, and coupled with the damages done to his health by the typhoid he suffered as a youth, Maxfield and Lydia found it necessary to seek out other climates, spending time in the Adirondacks, Arizona, and Italy. (The dry, vibrant landscape of Arizona has often been said to be a key influence for Parrish’s distinctive style and vibrant hues.) Eventually, though, they found themselves resettled in New Hampshire, where their lives would take a very different turn, after they hired a 16-year old girl named Susan Lewin.

Susan was initially hired to assist Lydia Parrish with the care of the Parrish children. (Perhaps due to Maxfield’s health concerns, the Parrishes waited until relatively late in life, for the time, to have children, with Lydia being almost 40 when their youngest child was born.) Susan quickly became Maxfield’s model and assistant, and eventually, they began an affair. Estranged from Lydia, who continued to live in the main house on the property, Maxfield ultimately moved into his studio where he lived with Susan.

Susan certainly must have served as a muse, because Parrish’s popularity skyrocketed in the years between 1905 and 1920. His art was in demand by publishers (he did dozens of covers for Collier’s) and advertisers from Colgate to Oneida, and he also had murals commissioned by wealthy patrons like Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney. Another mural, created in the Tiffany studio, incorporated 100,000 pieces of Tiffany glass, and drew the attention of Cyrus Curtis, the owner of the Saturday Evening Post, who commissioned a mural for the Post’s Philadelphia headquarters. (Many of Parrish’s murals still decorated the public spaces they were designed for, and visitors can see them in places as varied as the Curtis Building in Philadelphia and the St. Regis’s bar in New York.)

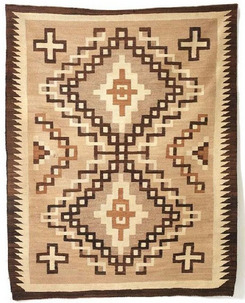

Success allowed him to shift his focus away from advertising by the mid-1920s. (He was so well-known that by 1925, it was estimated that 25% of the homes in America owned a Parrish print and the deep lapis lazuli blue he favored had become known as “Parrish blue,” hints of which are visible in the image above.) Parrish chose to move toward painting works of art that reflected, in some ways, his first job as an illustrator, and in many ways, this is the era of work for which Parrish is best remembered, androgynous, mystical figures in fantasy landscapes. By 1931, he announced that he was changing directions yet again, concentrating this time on landscapes.

In 1953, Lydia, who had for the most part left Maxfield in 1911, died, and he was left alone with Susan. Susan, perhaps frustrated by Maxfield’s lack of interest in marrying her after so many years together, left to marry someone else in 1960, and it was at that point that Maxfield Parrish stopped painting at the age of 90. He remained at The Oaks in Plainfield, New Hampshire until his death at 95 on March 30, 1966.

![Basket; Eskimo, Bogenrife (Sheldon), Round, Ivory Seal Finial, 2 inch. Baleen basket by Sheldon Bogenrife (Inuit, 20th-21st century), finely woven basket topped with a delicately carved [ivory] seal finial](http://www.prices4antiques.com/item_images/medium/67/89/97-01.jpg)

![Stoneware; Norton (J&E), Jug, Cobalt Pheasant Decoration. J. and E. Norton, Bennington, Vermont stoneware [salt-glazed pottery] jug with double pheasants](http://www.prices4antiques.com/item_images/medium/68/08/83-01.jpg)