Theodore Clement Steele oil painting, Early Indiana Landscape with Cows. Sold by Jacksons Auction Company in 2008.

When Dennis Jackson held his first Indiana art auction in 1981, he was told the event would never succeed. Thirty years later, Jackson is still specializing in artwork by Hoosier painters. And, interest remains strong.

On March 27 Jacksons Auction Company will conduct its latest art sale. At the same time, the firm will celebrate the 30th anniversary of its initial art auction.

Jackson didn’t set out to sell Indiana art. When he founded Jacksons Auction Gallery in an old barn on the outskirts of Anderson, Ind., in 1978, oak furniture was the focus of many of his sales. He realized he could buy oak reasonably in Indianapolis and sell it for a profit in Anderson.

While at one downtown Indianapolis warehouse auction in order to buy furniture, Jackson watched an Indiana painting sell for $2,500. The event resulted in an epiphany.

“I’m standing there in shock, thinking, Dennis Jackson, you’re not very smart,” he recalled. “I realized at that point in time I’d moved a complete estate in Anderson, and it brought $2,500.”

If bidders were willing to spend that kind of money on paintings by Indiana artists, then Jackson wanted in on the action. “I am going to see about selling Indiana art in Indiana,” he said.

There was only one problem — he was largely unfamiliar with the subject.

“I knew what an oil on canvas was and an oil on board. I knew who T.C. Steele was,” he said. But that was about the extent of his knowledge.

As a former teacher, he wasn’t discouraged. “I realized I needed to learn about art,” he said.

“I immediately bought every Indiana book I could find and read them. I was not an art expert as such. I realized I had a good eye — that’s God-given. I just did not have any background.” He asked a lot of questions, with knowledgeable dealers patiently helping him.

Yet, not everyone was enthusiastic about the idea of an Indiana art auction.

“Everybody said, ‘It will not work.’”

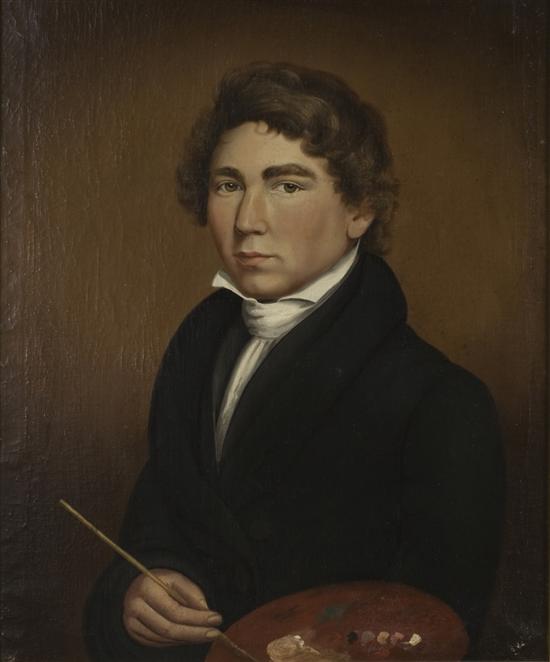

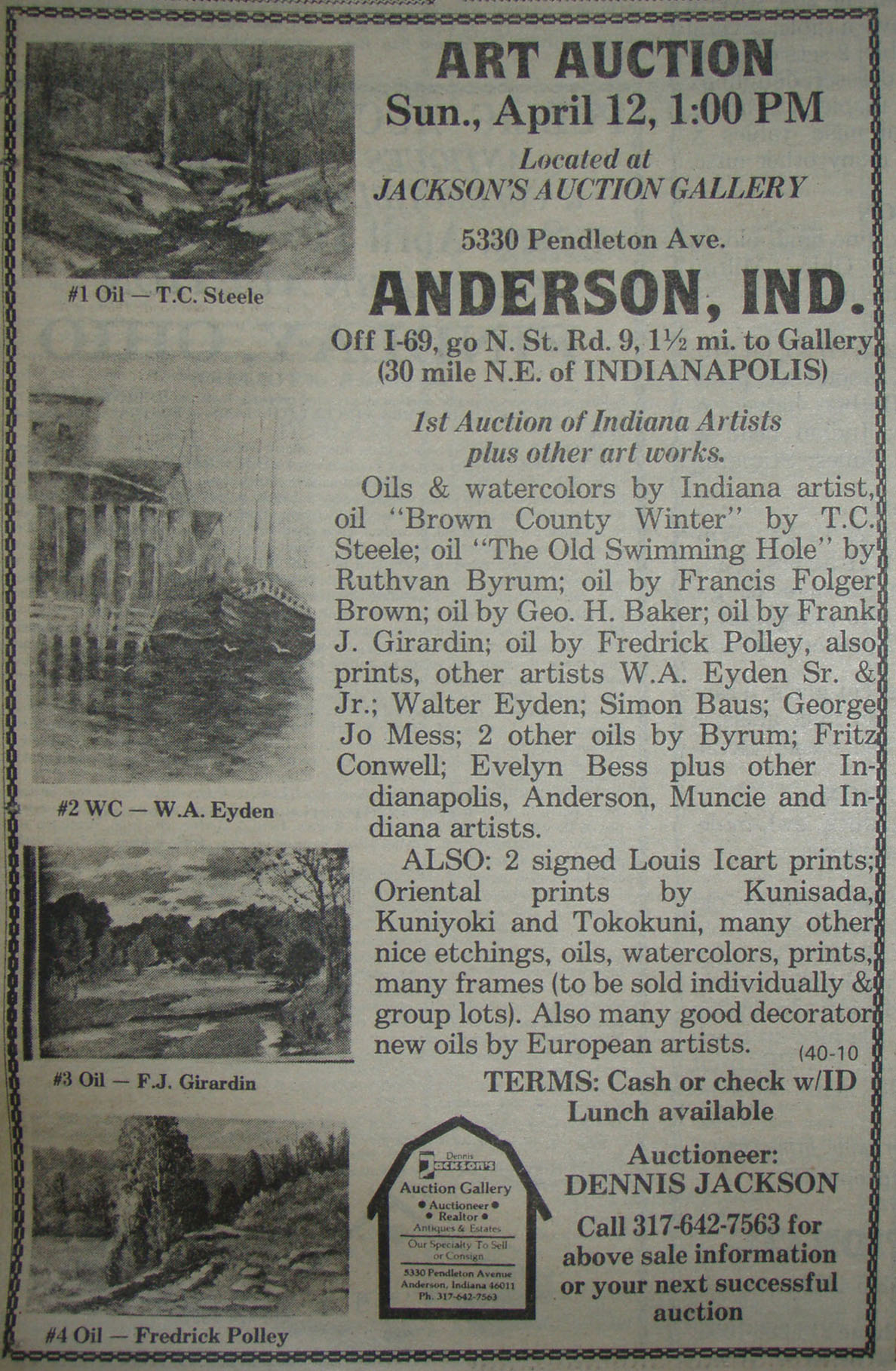

Although he had to borrow money to buy paintings to fill the sale, Dennis Jackson's investment paid off. This ad promoted that first auction, held April 12, 1981.

At first, they seemed to be right. When Jackson placed an ad in Tri-State Trader (now AntiqueWeek), seeking consignments for the first Indiana art auction, he got only two. One was a small snow scene by Theodore Clement Steele, the state’s most noted painter. The other item — a Louis Icart etching — was French.

Discouraged but not deterred, Jackson took the initiative.

“I borrowed money from the bank, and I went out and bought all the Indiana signed paintings that I could find for $200 or less. I ended up with about 35 paintings, with that T.C. Steele being the lead.”

The auction was held on April 12, 1981. Paintings sold that day included landscapes by Frank J. Girardin and Frederick Polley, as well as a W.A. Eyden dock scene. As anticipated, however, it was the Steele that brought the most interest, realizing $3,400.

Jackson followed up the event with a second Indiana art auction, a 50-painting sale that September. In March 1982 he put together a 100-lot auction of Indiana art, clearly having found a niche market. The artists represented read like a Who’s Who of Indiana art — Steele, J. Ottis Adams, William Forsyth, Otto Stark, R.B. Gruelle, Will Vawter, V.J. Cariani, Glen Cooper Henshaw, Gustave Baumann and more.

For the first several years the company held two auctions annually, in March and September, then added a third sale in November and eventually a fourth in June. Each auction averaged about 100 lots.

In 1992 Jackson joined forces with Sue Wickliff, opening Jackson & Wickliff in Carmel, Ind. While there, he continued to specialize in Indiana art, while also selling a variety of antiques. When the partnership ended in 2004, Jackson contemplated giving up his art sales. However, a fortuitous phone call persuaded him to keep at it.

The call was from a friend who wanted to consign a painting by Steele to one of Jackson’s art auctions. It came as Jackson was cleaning out his office at the Carmel auction gallery. Jackson explained he was no longer selling art in Indianapolis.

“The guy said, ‘I don’t care where you’re at, I want you to sell it.’”

Jackson called his son Bryan, who had been a part of the family’s auction business since he was a child. They decided to continue with Indiana art auctions. Within two months they had 50 consignments and had found a new site on Zionsville Road in Indianapolis to serve as their gallery. The resulting sale, held in May 2004, was followed by another in September. The following year they conducted three art auctions. Consignments continued to come in, with the firm now holding six Indiana art sales annually.

The business hit a slight snag when Bryan, a mental health specialist in the Army, was deployed to Iraq for a year in 2005 to 2006. However, the younger Jackson kept involved overseas by cropping art photos emailed to him from his dad in Indiana. When he returned to the states, Bryan initially planned to attend radiology school. But, during a three-month wait leading up the program, he helped for his father and discovered along the way that he enjoyed the auction business.

“He came to me and said, ‘Dad, I like the auction thing,’” Dennis Jackson recalled. Bryan dropped the idea of radiology school, electing to stay in Indianapolis to work for his father. However, that soon changed.

When Dennis Jackson turned 60, he approached his children, Bryan and Michele (also a licensed auctioneer who had helped with the firm) and encouraged them to form a new company. “I want to work for you,” he told them.

In 2006 the siblings formed Jacksons Auction Company, continuing the tradition started by their father, with Indiana art playing an integral role in the business.

-Don Johnson, p4A.com

originally published in AntiqueWeek, March 2011.