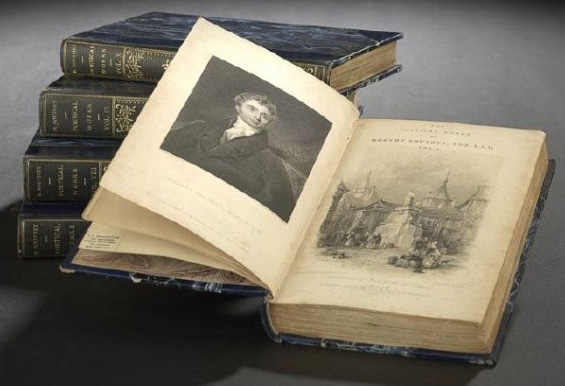

You may not be able to judge a book by its cover, but you can at least tell its size, but to do that, you have to know a little bit about the printing process, which basically, at least when it comes to paper sizes, has two eras: the modern era and the hand press era. In the hand press era (pre-1820, for the most part), printing was done on large sheets, on both sides, and then the sheets were folded and stitched along the folds. (The spatial reasoning necessary to lay out a sheet’s worth of printing, knowing which way the text would appear and the pages would be ordered when folded, is impressive.) Each set of pages created from the same folded sheet was called a gathering and multiple gatherings would all be bound together to create the finished book. Sometimes the edges of the gathering were trimmed on the three exposed sides, but in early books, you might have to use a knife to slice through the folds of the gathering to separate each page yourself.

You may not be able to judge a book by its cover, but you can at least tell its size, but to do that, you have to know a little bit about the printing process, which basically, at least when it comes to paper sizes, has two eras: the modern era and the hand press era. In the hand press era (pre-1820, for the most part), printing was done on large sheets, on both sides, and then the sheets were folded and stitched along the folds. (The spatial reasoning necessary to lay out a sheet’s worth of printing, knowing which way the text would appear and the pages would be ordered when folded, is impressive.) Each set of pages created from the same folded sheet was called a gathering and multiple gatherings would all be bound together to create the finished book. Sometimes the edges of the gathering were trimmed on the three exposed sides, but in early books, you might have to use a knife to slice through the folds of the gathering to separate each page yourself.

In this system of printing, page sizes were determined by how many times the original sheet was folded. A folio (2° or fo) would been folded once, down the center, and with two pages of text printed on either side, it would create four printed pages. This is designated as the “format” of the book. Quartos (4° or 4to) would be folded twice to produce four leaves/eight pages, octavos (8° or 8vo), three times for eight leaves/16 pages, etc., with the sizes continuing through duodecimo (twelvemo – 12° or 12vo), sextodecimo (sixteenmo – 16° or 16vo), octodecimo (eighteenmo – 18° or 18vo), trigesimo-secundo (thirty-twomo – 32° or 32vo), quadragesimo-octavo (forty-eightmo – 48° or 48vo) and sexagesimo-quarto (sixty-fourmo – 64° or 64vo).

One challenge with deciphering this is that in the hand press age in particular paper sizes were not typically standardized or, if they were, it was only within a particular region or country of manufacture. As a result, sizes of quartos, for example, can vary because while all quartos have gatherings that are folded twice, the size of the original sheet can vary. This means that quartos printed in Italy and quartos printed in England in the same time period can be different sizes.

In modern production, sizes are standardized and most books are quartos or octavos. There are designations for less typical sizes as well, which are heard more commonly in reference to prints than books: elephant folio, atlas folio and double elephant folio. As with all paper objects, condition is paramount, with size playing the largest role when it comes to prints but little role at all with books. In fact, most sellers do not give physical dimensions for books, as historically, much like today, books were not printed in multiple sizes at the same time and the other information: place of publication, year, etc., is more useful to collectors. Determining the rarity of books typically has more to do with when and where they were printed and what edition a volume is than the size, although of course, this does not necessarily apply when the books are out of the traditional size range. And books do not change sizes as prints can, so more on the specifics of paper sizes related to prints in our next post….