We take the availability of art all around us for granted. That’s part of post-modernism, the fact that there’s no real original now, but just a stream of copies. There are sites all over the Internet offering inexpensive poster copies of great works of art, but until roughly the mid-19th century, artwork in homes was limited, both in quantity and quality. Wealth made it possible to commission portraits and landscapes from a variety of artists, from itinerants with varying levels of talent and training to professional, established painters, but the average home had limited options for decoration.

We take the availability of art all around us for granted. That’s part of post-modernism, the fact that there’s no real original now, but just a stream of copies. There are sites all over the Internet offering inexpensive poster copies of great works of art, but until roughly the mid-19th century, artwork in homes was limited, both in quantity and quality. Wealth made it possible to commission portraits and landscapes from a variety of artists, from itinerants with varying levels of talent and training to professional, established painters, but the average home had limited options for decoration.

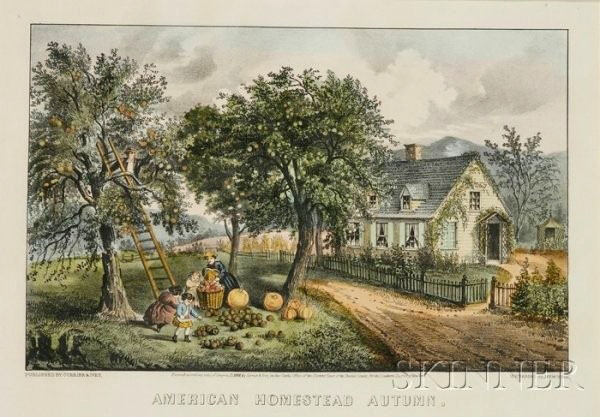

Until Nathaniel Currier and James Merritt Ives came along. Technically, they didn’t actually come along at the same time. Currier started doing lithographs in 1834, set up his own shop in 1836, and worked under his name alone until 1857, when Currier invited Ives, his bookkeeper/accountant (and husband of his brother’s sister-in-law – nepotism never goes out of fashion), to join him as a partner, after he recognized not only Ives’ business abilities, but his artistic sensibilities and awareness of what had mass appeal. And the presses began to roll even more quickly….

The firm, which advertised “cheap and popular prints,” back when “cheap” was a good thing, produced at least 7,500 lithograph images (and hundreds of thousands of copies of those) over the full 72 years of Currier operations, lithographic images that captured every single aspect of American life – from politics, travel, disasters, and sports to the bucolic and pastoral scenes of the American countryside and home life (I’m partial to the “Homestead” series – fall is pictured above) for five cents to three dollars, depending on size and subject matter. Currier and Ives were not artists, but rather commissioned or bought the work of artists that they then had converted to prints and (depending on the image) hand-colored. (The firm employed some of the greatest artists of the era, including names like George Inness, Eastman Johnson and Thomas Nast.) While Currier & Ives images are often dismissed out of hand for their sentimental view of American life, they actually tell the tale of America’s democratic nature, of the individual, and leave an incredible record of the images we found most appealing and enduring of ourselves. They are, in a sense, the illustrations for the story Americans, both today and in the past, told themselves about themselves, the depictions of our own mythology in progress.

Thanks to Frederic Conningham, a man who must have had the soul of a librarian, Currier & Ives prints are very well organized for today’s collector. Conningham assigned each print a number, tracked the various sizes in which the image was produced, and generally laid an organized foundation for the future study and appreciation of the images, but even today, new discoveries of obscure images turn up. Value is based primarily on size, subject matter, rarity, and, as with all things paper and mass-produced, also heavily dependent upon condition. Definitely worth taking note the next time you see one, if for no other reason than the fact that they sort of are America’s self-portrait!