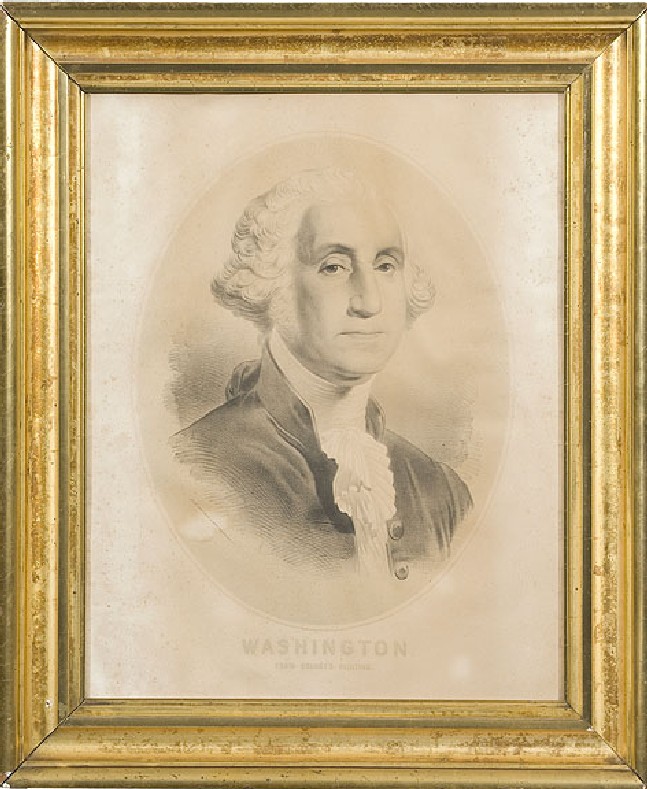

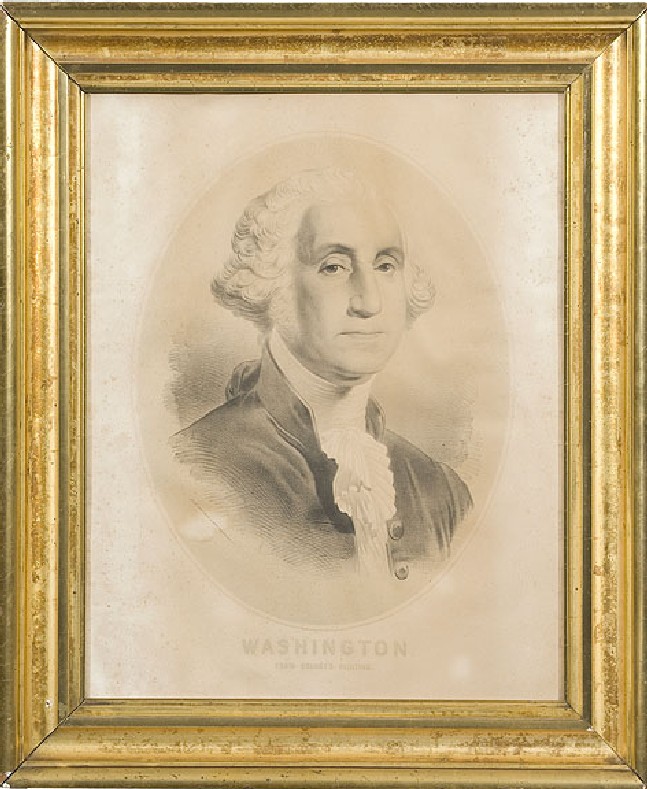

Lithograph of George Washington based on a Gilbert Stuart portrait.

The word lithography comes from Greek lithos, meaning “stone” and grapho, meaning “writing.” Although “stone writing” is sometimes done today with a metal plate, traditionally the process gets its name from the use of limestone.

Lithography is made possible by one of the simplest scientific phenomena – the repelling relationship between water and oil. A hydrophobic (water-repelling) substance with a fat or oil base is used by the artist to draw the image directly on the plate, and then the plate is washed with a hydrophilic (water-drawing) solution. The plate is kept wet during printing, and the water moves to the hydrophilic blanks, repelling the oil-based printing inks toward the hydrophobic design. While a variety of options exist for hydrophobic materials, the key to success is a substance with oils that stand up to the presence of water and acid. A weak hydrophobic substance contributes to a lack of crispness in the plate image and thus in the resulting printed images.

This process was invented by Aloys Senefelder, a Bavarian writer, in the 1790s, and Senefelder predicted, but did not truly pioneer, the successful use of color that would blossom in the early 19th century. Introducing color to the process was the work of Godefroy Engelmann in the 1830s. Color lithography, known as chromolithography, requires the artist to break the image down into colors, creating a separate plate for each color to be applied. The challenge with chromolithography, and one of the key measures of quality, is how carefully the plates are aligned for each application. This is referred to as “registration” or being “in register,” revealing the care and attention to detail supplied by the printer.

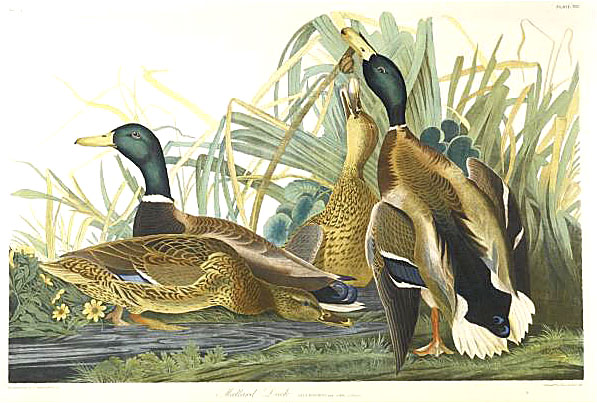

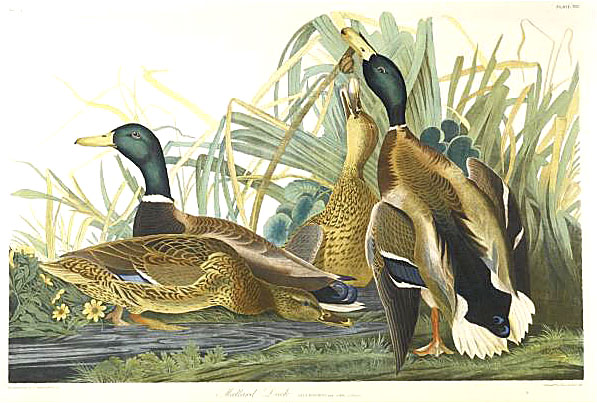

While originally intended mostly for the creation of images, lithography soon became a popular method for printing texts, especially those in Arabic and other scripts where the characters are linked in a way that makes movable type less than ideal. The richness of chromolithography was not lost on artists, however, and found popularity throughout the 19th century, especially among French artists like Edgar Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec and in nature prints like those inspired by John James Audubon.

While stone is no longer the basis for the process, making “lithography” somewhat of a misnomer, lithographic printing is still widely used today. In fact, it is the method by which most modern mass printing is done. Today, the process involves a photographic process and flexible plates of aluminum, polyester or even paper. A photographic negative of the desired image is created and applied to a plate coated in a light-sensitive emulsion. Exposure to ultraviolet light creates a reverse of the negative reverse – a positive of the original image – on the plate. This transfer of images is also sometimes accomplished with the use of laser technology, but in the end the process remains the same: water is applied and rejected by the emulsion, hydrophobic ink moves toward the areas of design, and the basic conflict between oil and water continues to produce most of our books, newspapers, and magazines!

While stone is no longer the basis for the process, making “lithography” somewhat of a misnomer, lithographic printing is still widely used today. In fact, it is the method by which most modern mass printing is done. Today, the process involves a photographic process and flexible plates of aluminum, polyester or even paper. A photographic negative of the desired image is created and applied to a plate coated in a light-sensitive emulsion. Exposure to ultraviolet light creates a reverse of the negative reverse – a positive of the original image – on the plate. This transfer of images is also sometimes accomplished with the use of laser technology, but in the end the process remains the same: water is applied and rejected by the emulsion, hydrophobic ink moves toward the areas of design, and the basic conflict between oil and water continues to produce most of our books, newspapers, and magazines!

“Vermeil” is a French word co-opted by the English in the 19th century for a silver gilt process. Vermeil is a combination of silver and gold, although other precious metals are also occasionally added, that is then gilded onto a sterling silver object. The reddish (vermilion) hue of the addition of the gold gives the product its name. Vermeil is commonly found in jewelry, silver tablewares, and small decorative objects and a standard of quality (10 karat gold) and thickness (1.5 micrometers) has been set with regard to jewelry.

“Vermeil” is a French word co-opted by the English in the 19th century for a silver gilt process. Vermeil is a combination of silver and gold, although other precious metals are also occasionally added, that is then gilded onto a sterling silver object. The reddish (vermilion) hue of the addition of the gold gives the product its name. Vermeil is commonly found in jewelry, silver tablewares, and small decorative objects and a standard of quality (10 karat gold) and thickness (1.5 micrometers) has been set with regard to jewelry.

![Hunting; Duck Call, Perdew (Charles), Carved, Flying Mallards. A carved [duck hunting] duck call by Charles Perdew (1874 to 1963) of Henry, Illinois.](http://www.prices4antiques.com/item_images/medium/60/44/61-02.jpg)