![Stoneware; Norton (J&E), Jug, Cobalt Pheasant Decoration. J. and E. Norton, Bennington, Vermont stoneware [salt-glazed pottery] jug with double pheasants](http://www.prices4antiques.com/item_images/medium/68/08/83-01.jpg) One of the most iconic objects from 18th- and 19th-century is stoneware, particularly pieces with cobalt decoration, and few people did cobalt-decorated salt-glazed stoneware pottery better than the Norton family of Vermont.

One of the most iconic objects from 18th- and 19th-century is stoneware, particularly pieces with cobalt decoration, and few people did cobalt-decorated salt-glazed stoneware pottery better than the Norton family of Vermont.

The Norton pottery dynasty actually predates Vermont’s statehood, founded as it was by Captain John Norton in 1785, although stoneware was not what was initially manufactured. Unmarked redware pieces were the earliest offerings and salt-glazed stoneware soon followed, with utilitarian wares being offered throughout the region. The stoneware pieces from this period were marked “Bennington Factory,” and while the occasional piece seems to have had some simple incised or cobalt decoration, most pieces were just “decorated” with a cobalt script number, if at all.

By 1812, Luman Norton, Captain Norton’s oldest son, joined the business and in 1823, Captain Norton had left the company in the hands of Luman and his brother John. Pieces with “L. Norton & Co.” date from the brothers’ era, an era that was short-lived as Luman was in business by himself by 1828, when he marked pieces simply, “L. Norton.”

Julius Norton, Luman’s son, would join his father in business in 1833, a fact reflected in the mark, “L. Norton & Son,” which was used until Luman’s retirement in 1841, at which point Julius managed the pottery solo under “Julius Norton.”

Four years later, in 1845, Julius Norton took a partner, his brother-in-law, Christopher Fenton, but again, the partnership of “Norton & Fenton” was short-lived, lasting only two years until 1847, when Fenton left and Julius again operated as “Julius Norton” until the end of the decade.

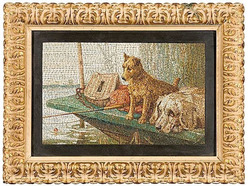

The 1850s ushered in a new partnership and what would be the pottery’s golden age. Edward Norton, a cousin, began to work with Julius in the management of the firm, now marking wares as “J. & E. Norton.” It was during this period that the detailed cobalt decorations Norton became known for, the ones often seen as most desirable among collectors today, were produced, particularly pieces with deer, elaborate birds of various kinds, and scenes with buildings like schoolhouses. (Like the impressive example pictured above.)

The firm changed structure – and marks – again in 1859, when Julius’s son Luman Preston Norton came on board, an era in which the pieces produced were marked “J. Norton & Co.,” but in 1861, Julius died and Luman Preston Norton and Edward Norton continued working as “E. & L.P. Norton,” in a partnership that would prove to be one of the most stable in Norton history.

By 1881, twenty years later, however, perhaps Luman realized that stoneware’s role in the marketplace was dwindling, but whatever the reason, he left the pottery and Edward Norton continued work as “E. Norton & Co.” for another two years before selling half of the business to C.W. Thatcher of Bennington, the first “non-family” owner the business had had in nearly a century. Edward Norton died two years after this in 1885, at which point his son Edward Lincoln Norton took over his portion of the business. From 1883 on, pieces were manufactured by “The Edw’d Norton Co.,” but the company continued to decline. Efforts were made to diversify and for a time, the firm sold glass and other forms of pottery wholesale, but the heart of the business, the stoneware manufacturing, continued to decline steadily. By the time of Edward Lincoln Norton’s death in 1894, stoneware production had ceased and while C.W. Thatcher would carry on selling similar wares into the 20th century, the Norton family dynasty had ended.

Norton pottery pieces remain popular with stoneware collectors today, and unlike some potteries where price is driven by the rarity or unusual nature of the form, since the majority of Norton wares were traditional utilitarian objects, value is predicated on the quality and subject matter of the decoration. Pieces with elaborate, intricate decoration command strong prices, and the strongest Norton prices are reserved for pieces with atypical subject matter: houses, horses, and less frequently seen birds like peacocks, pheasants, and hawks.

Norton Pottery Marks:

L. Norton (1828-1833)

L. Norton & Son (1833-1841)

Julius Norton (1841-1850)

Norton & Fenton (1845-1847)

J. & E. Norton (1850-1859)

J. Norton & Co. (1859-1861)

E. & L.P. Norton (1861-1881)

E. Norton & Co. (1881-1885)

The EDW’D Norton Co. (1885-1894)

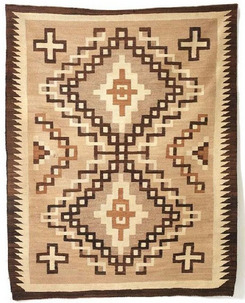

In 1896, Texas-born John Bradford Moore, the former mayor of Sheridan, Wyoming, purchased the seasonal trading post at Narbona Pass in New Mexico. He erected a permanent log building and established the Crystal Trading Post.

In 1896, Texas-born John Bradford Moore, the former mayor of Sheridan, Wyoming, purchased the seasonal trading post at Narbona Pass in New Mexico. He erected a permanent log building and established the Crystal Trading Post.

![Stoneware; Norton (J&E), Jug, Cobalt Pheasant Decoration. J. and E. Norton, Bennington, Vermont stoneware [salt-glazed pottery] jug with double pheasants](http://www.prices4antiques.com/item_images/medium/68/08/83-01.jpg)