Joseph Marie Charles (1752-1834) never really bore the surname that has been applied to his loom. Rather Jacquard was a nickname of sorts given to his family’s particular branch of all the Charleses in Lyon during the 18th century. Despite the family’s prosperity (his father was a master weaver), Joseph had very little education and did not learn to read until he was a teenager. Joseph’s father died when Joseph was 20, but it is unknown how he spent much of his early adult life.

Joseph Marie Charles (1752-1834) never really bore the surname that has been applied to his loom. Rather Jacquard was a nickname of sorts given to his family’s particular branch of all the Charleses in Lyon during the 18th century. Despite the family’s prosperity (his father was a master weaver), Joseph had very little education and did not learn to read until he was a teenager. Joseph’s father died when Joseph was 20, but it is unknown how he spent much of his early adult life.

Historians are fairly confident that he married in 1778, had a son in 1779, fled the spreading rebellion in Lyon in 1793, and joined the revolutionary army, where his son would die in battle. By 1800, Joseph had returned to the family tradition and was experimenting with innovative new ideas – including the Jacquard loom, which could be “programmed” to weave pattern. Although there was opposition from weavers who felt they would lose their work and there were technical glitches that would not be resolved until 1815, the potential of his loom was immediately recognized and the French government awarded Jacquard a pension and royalties on machines.

In traditional weaving, warp threads are stretched up and down on a loom, while weft threads run at right angles to the warp through the “shed” or the gap created between the lower and upper warp threads, which are raised and lowered by the operation of the loom in between passing the weft threads across back and forth through the shed. For plain cloth, this is simple – every other warp thread is raised and over hundreds and thousands of passes of the shuttle of weft threads, the cloth is built up. Then it gets complicated… By raising warp threads in different orders and by changing out the colored threads in the weft, a weaver can create a wide variety of textures, patterns, colors and even designs, but the process is slow and complicated. Jacquard’s loom, which used punched cards with rows for each row of the design that were then strung together in order, aimed to expedite the process and eliminated common errors, building on the work of more than 70 years’ of contributions from other French weavers, none of whom had been able to create systems that would execute textiles complex enough to justify the expense and the learning curve. But Napoleon was eager to incentivize improvements in the French textile industry in order to trump Britain’s textile business, Jacquard had the work of several other key inventors to build on, and his success was quickly recognized.

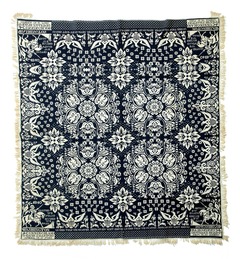

Jacquard coverlets in America are occasionally seen from the 1820s, but 1830s dates are much more common. The production of Jacquard pieces in the United States would hit its peak in the 1840s and 50s, but would taper off fairly rapidly with the equally dramatic rise of New England textile mills. As with all textiles, condition is important. While there were looms large enough to accommodate the full width of a coverlet, most were woven on smaller looms, necessitating the weaving of two separate panels that were then stitched together along the center – the same center line along which they were often folded. As a result, coverlets are often found with split or fraying areas down the middle. Weavers would frequently sign and/or date the corner blocks and these coverlets tend to be more desirable, as are the rarer patterns with railroad or steamboat imagery (as opposed to the much more common flower or bird motifs).

Values for coverlets have softened over the past decade. Textiles always require a different kind of commitment than many antiques, as they cannot be used, and coverlets in particular are difficult because they are woven, meaning they pick easily, and they are wool, so they collect dust and pet hair. Coverlets in rough condition can bring as little as $10-$25, while most fetch between $300-$700 at auction, although ones with rare designs or from areas with few documented examples can still get to $1,000-$3,000 on the auction block.