Chamfer is derived from a French word that means exactly what it means in the current usage: a beveled edge. In terms of furniture, a chamfer is a shaped edge where two pieces of wood meet. A chamfered edge refers to what is typically a 45-degree cut on a corner, which results in a softening of the corner. When a corner is softened with a “convex” rounded edge, it’s referred to as a bullnose. Oftentimes in furniture with exterior chamfering on the corners, the cut tapers out at the ends, which is called a variety of things including lamb’s tongue or lark’s tongue. (Some distinguish a lamb’s tongue from a lark’s tongue by using lark’s tongue for a plain, smooth tapered end and lamb’s tongue for tapering that includes a bit of a step and curl at the end.) Exterior chamfers are also sometimes decorated with reeded carving, like the one pictured above. Chamfering on the interior of a piece tends to refer to rough shaping on the panels in doors to taper the panels down to fit the joint. This sort of chamfering also appears on other unseen places including drawer bottoms and case backs. Chamfering, particularly interior chamfering with a hand plane, is one of the most obvious indicators that a piece was handmade instead of mass produced.

Chamfer is derived from a French word that means exactly what it means in the current usage: a beveled edge. In terms of furniture, a chamfer is a shaped edge where two pieces of wood meet. A chamfered edge refers to what is typically a 45-degree cut on a corner, which results in a softening of the corner. When a corner is softened with a “convex” rounded edge, it’s referred to as a bullnose. Oftentimes in furniture with exterior chamfering on the corners, the cut tapers out at the ends, which is called a variety of things including lamb’s tongue or lark’s tongue. (Some distinguish a lamb’s tongue from a lark’s tongue by using lark’s tongue for a plain, smooth tapered end and lamb’s tongue for tapering that includes a bit of a step and curl at the end.) Exterior chamfers are also sometimes decorated with reeded carving, like the one pictured above. Chamfering on the interior of a piece tends to refer to rough shaping on the panels in doors to taper the panels down to fit the joint. This sort of chamfering also appears on other unseen places including drawer bottoms and case backs. Chamfering, particularly interior chamfering with a hand plane, is one of the most obvious indicators that a piece was handmade instead of mass produced.

You are currently browsing the archive for the Furniture category.

Examining a piece of furniture is like examining a crime scene – forensics play a role in unraveling puzzles about the who, what, where, when, how of each object. One of the “fingerprints” commonly found in pieces of furniture is the dovetail joint (also known just as dovetail or, in Europe, often called a swallowtail or fantail joint). The photograph here shows the front corner of a drawer in a chest. The chest itself is also dovetailed. While no one really knows how old the dovetail joint is, some of the earliest examples are from pieces found in ancient tombs, both in China and in Egypt.

Examining a piece of furniture is like examining a crime scene – forensics play a role in unraveling puzzles about the who, what, where, when, how of each object. One of the “fingerprints” commonly found in pieces of furniture is the dovetail joint (also known just as dovetail or, in Europe, often called a swallowtail or fantail joint). The photograph here shows the front corner of a drawer in a chest. The chest itself is also dovetailed. While no one really knows how old the dovetail joint is, some of the earliest examples are from pieces found in ancient tombs, both in China and in Egypt.

Dovetails are used in the construction of furniture as well as buildings as joining techniques in a way that offers impressive tensile strength. A dovetailed joint is like interlaced, interlocking fingers. (They’re technically referred to as “pins” and “tails.”) These fingers have a wedge or trapezoidal form and are glued together when finished, meaning an entire piece of furniture – or even an entire log cabin – can be assembled without so much as a single nail!

While most catalogers rarely make the distinction, dovetails can be accomplished in several ways – through, half-blind, secret mitered, sliding and full blind. In specific instances with a large enough body of work to compare, they can link objects to a particular cultural group, a specific shop or even identify the hand of a particular maker. (For instance, English dovetails are often perceived to be finer and more delicate, while Germanic ones tend to be seen as wider and more robust, but even this changes over time and in communities where both populations worked together or other factors influenced the practices of a local shop.)

In the early days of more industrial furniture production, dovetails were still handcut, banged out from templates in the kind of repetitive work that fell to apprentices and journeymen, but by the early 20th century, factories had figured out how to cut dovetail pin and tail wedges with machines. Around this same time, machine-cut joints, fashioned with rectangular pins and tails versus the traditional wedges, began to appear. While occasionally misidentified, these are technically not dovetails, as dovetails draw their very name from their wedge-like resemblance to a bird’s tail, but finger joints.

Canterbury is one of those terms that, when the piece to which it originally applied fell out of fashion, was simply picked up and applied a second time to another form that was at least in some ways similar to the original. A canterbury in the 18th century was a low wooden stand, typically on casters, with a divided top, the purpose of which was to be set near the dining table and hold plates and cutlery. The form’s name is said to be a nod to the Archbishop of Canterbury who was an early adopter.

Canterbury is one of those terms that, when the piece to which it originally applied fell out of fashion, was simply picked up and applied a second time to another form that was at least in some ways similar to the original. A canterbury in the 18th century was a low wooden stand, typically on casters, with a divided top, the purpose of which was to be set near the dining table and hold plates and cutlery. The form’s name is said to be a nod to the Archbishop of Canterbury who was an early adopter.

At some point, someone took the idea of the divided tray, deepened the wells, and, in some cases, added more compartments to create another portable piece of furniture, this one with slatted spaces for most typically sheet music or magazines and newspapers. These pieces are the forebearers of the modern magazine rack and in typical Victorian fashion, the form gets more elaborate as the 19th century wears on. By the latter part of the century, canterburies have end panels with music-inspired shapes (treble clefs or lyres/harps) and an upper shelf or tray top has been added.

Canterburies still have solid value with collectors, as they remain very useful for holding the exact things they were originally designed to hold and because they were used for the better part of two centuries at the very least, they’re available in a variety of styles and conditions.

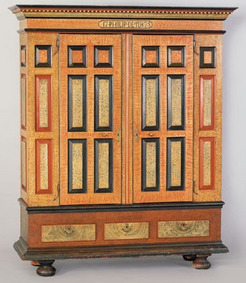

Schrank is a German word that is actually a diminutive form or abbreviation of Kleiderschrank. (Kleider means “clothes” and schrank means “cabinet,” so literally a clothes cabinet.) These massive pieces of furniture (schrunken is the plural), like the one pictured here, are essentially wardrobes that were made in America in Germanic settlements in Pennsylvania and then later in the Midwest and Plains states. It is speculated that they were often “coming of age” pieces or wedding gifts to couples setting up housekeeping together, because they frequently appear with names or initials and are often dated. Pennsylvania Germans typically made them in cherry and walnut often with very “architectural,” dramatic panels and/or decorated them with light wood and sulphur inlay. When “plainer” woods such as pine and poplar were used, they were often painted with vibrant colors. The example here has all the classic elements of a schrank: heavily paneled; elaborate cornice; paint decoration in red, yellow and green (a popular color scheme in Germanic communities); and a name and date.

Schrank is a German word that is actually a diminutive form or abbreviation of Kleiderschrank. (Kleider means “clothes” and schrank means “cabinet,” so literally a clothes cabinet.) These massive pieces of furniture (schrunken is the plural), like the one pictured here, are essentially wardrobes that were made in America in Germanic settlements in Pennsylvania and then later in the Midwest and Plains states. It is speculated that they were often “coming of age” pieces or wedding gifts to couples setting up housekeeping together, because they frequently appear with names or initials and are often dated. Pennsylvania Germans typically made them in cherry and walnut often with very “architectural,” dramatic panels and/or decorated them with light wood and sulphur inlay. When “plainer” woods such as pine and poplar were used, they were often painted with vibrant colors. The example here has all the classic elements of a schrank: heavily paneled; elaborate cornice; paint decoration in red, yellow and green (a popular color scheme in Germanic communities); and a name and date.

This summer Prices4Antiques, along with Garth’s Auctions, sponsored an antiques writing contest: “Biography of an Object”. This was a unique opportunity for writers of all ages to spark life into a selection of decorative and fine art objects, even some found in the p4A database! We will be posting the 3 first place essays here on our blog.

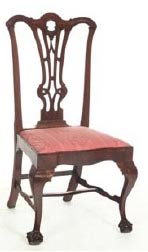

A Seat of Distinction

A Seat of Distinction

By Elaina C. of Xenia, Ohio

First Place: Child’s Division, Age 12 and Under

“Bang, bang, bang!” The carpenter hammered my intricately carved front legs on. I was filled with pain as he did it, for having one’s body parts screwed and hammered together is not a comfortable experience. The carpenter, I

discovered, had a habit of humming and talking himself as he worked and usually said things like, “Where did those nails go?” and, “Beautiful work, if I do say so myself!” What the carpenter didn’t know was that I could hear every word he said.

The next morning was dismal and rainy. Since the workshop was dark already, the carpenter lit some candles for light. Suddenly, a candle toppled to the floor and a pile of sawdust caught on fire. The carpenter untied his apron and beat the fire with it. The flames died down, and flickered out. The carpenter rushed over to me and examined me closely. Thankfully, there wasn’t a burn in sight.

At sunrise, the carpenter burst into his workshop and cried, “What a beautiful chair you are!” All day he hummed happy tunes, and his work was fast paced and efficient. “You’re going to be done this evening.” He said with a smile. Everything from my maroon upholstery to my clawed feet had been made with carefulness. Both the carpenter and I were pleased with the way I turned out. “Today is the day you are to be delivered,” the carpenter told me as he marched in at 5:00 the next morning. You would think he would be sad to part with the best work he had ever done, but he was actually happy to let someone use such a beautiful specimen for a good reason. I wondered who would own me. Would I live in a house with children? Would it be noisy or quiet? I certainly hoped I would be well‐kept. But neither he nor I would know until later what a wonderful purpose I was destined for.

At 7:00 that morning, I was delivered to a little house in Philadelphia. I was glad Philadelphia wasn’t far away, for the bumping of the wagon was loud and uncomfortable. When we got to the house, a quiet, red‐headed man was there to greet us. “Thank you very much for delivering this to me,” he said. The next evening, Thomas Jefferson sat down in me, and, at his desk wrote the opening line, “When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another…”