Stanford White (November 9, 1853 – June 25, 1906) was in his day best known for his Beaux-Arts work with the architectural firm of McKim, Mead & White, in which he was a partner, work which typifies what is thought of as the American Renaissance of art and design.

Stanford White (November 9, 1853 – June 25, 1906) was in his day best known for his Beaux-Arts work with the architectural firm of McKim, Mead & White, in which he was a partner, work which typifies what is thought of as the American Renaissance of art and design.

White’s family had no money, but were still well connected in the art world of New York in the 19th century, and through those connections, he began work as an assistant to Henry Hobson Richardson, who was perhaps the best-known architect in America at the time, and after several years with Richardson and an 18-month stint in Europe – and with no formal schooling, let alone training in architecture, White would return to New York and form his partnership with McKim and Mead.

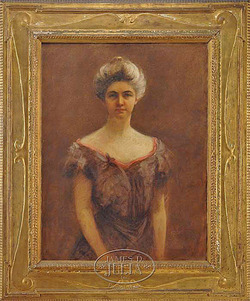

In 1889, White would design what might be his best-known work, the Washington Square arch, but he would also design numerous iconic buildings, both in New York City and throughout the United States. In addition to his public buildings (such as the Boston Public Library), he also designed many of the finest private homes in America at the time, including the Fifth Avenue mansions of the Astors and the Vanderbilts, as well as private clubs throughout the city. Like many prominent architects, McKim, Mead & White also had a hand in the interior furnishings of the homes they designed, and Stanford White’s designs also live on in the frames of Newcomb-Macklin, who would acquire the rights to White’s designs after his death.

Which would inevitably be what White was better known for. While very well-liked and well-connected socially, in fact a central figure in the New York City social scene, White also seduced and on occasion assaulted teenage girls. With New York in the heyday of burlesque, there were plenty of lovely chorus girls and aspiring models as conquests. Rumors of his red velvet swing swirled around the city, and these rumors, among other social incidents, would fuel an obsession with deadly consequences.

Evelyn Nesbit, who could barely be called one of White’s conquests, as he’d sexually assaulted her while she was 16 years old and unconscious to boot, had married Harry Kendall Thaw, a man whose lifelong mental instability was concealed by his Pittsburgh steel family fortune. Thaw’s dislike for White stemmed not only from his wife’s account of her interactions with the architect, but also from a myriad of social slights, mostly imagined or magnified by mental illness. In short, Thaw felt White had defiled Nesbit and thwarted his attempts at social climbing in the city, while White was likely oblivious to it all.

On June 25, 1906, both White and the Nesbit-Thaws were attending a show at the Madison Square Garden rooftop garden theater, when Thaw confronted White, drew a gun and said either “You’ve ruined my life” or “You’ve ruined my wife” before shooting White three times at close range, twice in the head and once in shoulder. Bystanders initially thought it was all a big prank, but White died almost instantly.

The trial, touted as “The Trial of the Century,” would be a media circus for the time, with the papers working every salacious angle to the story. Yellow journalism painted White as debauched and hedonistic, revisiting and questioning the value of his work. The tarnishing of White’s reputation when coupled with Thaw’s questionable mental state resulted in a verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity. Ironically, White’s autopsy revealed that he was suffering from three diseases which would have killed him in a relatively short period of time.

Today White’s name is most often associated with the Newcomb-Macklin frames which still fetch big prices at auction and are often more valuable than the art they contain.