Mathew Brady (1823 to 1896)

Mathew Brady, the child of Irish immigrants, was born in upstate New York in Warren County, but details of his early life are few. Even the year of his birth is an estimate that Brady later offered. Around the age of sixteen, he moved to New York City, making his living as a department store clerk and filling out his income with a small business manufacturing jewelry cases. Photography was just beginning to make an appearance in New York at the time, and young Brady picked up the study in his spare time. Apparently, he exhibited an amazing aptitude for the craft, because by 1844 he had opened his own studio. In 1845, he mounted an exhibition of portraits of his famous clients, and over the next few years, he also opened a studio in Washington, D.C. and met and married Juliette Handy.Brady's initial images were daguerreotypes, and he created an album, The Gallery of Illustrious Americans, that he published in 1850. While a financial flop, the album did earn Brady some attention and his images were exhibited at the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London in 1851. After winning one of the exhibition medals, Brady toured Europe, but sadly, at this time, he began to experience problems with his eyesight that would plague him for the rest of his life.

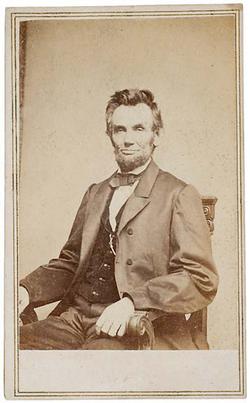

As his eyesight continued to deteriorate, in time making it virtually impossible for Brady to take photographs himself, Alexander Gardner appeared in his life, after encountering Brady's work at the Crystal Palace Exhibition. Before long, Brady had shifted the responsibility of running the Washington gallery to Gardner, who worked for Brady from 1856 until 1862. Brady would photograph his most important clients, including Abraham Lincoln, who often credited a Brady portrait of him for his 1860 victory.

A Brady-published photograph of Abraham Lincoln, taken in 1864. (p4A item # C228334)

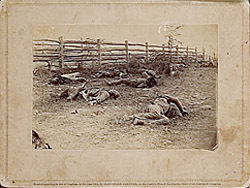

Like many other civilians, when the Civil War erupted, Brady was anxious to see the action in person, and the Battle of Bull Run, near Manassus, Virginia, and only about 30 miles from Washington, presented a wonderful opportunity. Traveling with a friend, Brady got closer to the action than he may have intended, and he was nearly captured in what turn out to be a devastating rout for the Union. Still, Brady returned to Washington convinced that it was vital to create a photographic record of the war. He had as many as twenty photographers, working in teams, outfitted with wagons that were converted to portable darkrooms; they had everything necessary to capture and develop images right on the front lines.

A Brady photograph of the dead at Antietam. (p4A item # D9997008)

War would seem to be good for Brady's business. His studio was ideally located to cater to not only the military elite (his patrons included virtually all of the 'big name' of the Civil War - McClellan, Sherman, Hooker, etc.), but to the hordes of soldiers moving through the city on their way to battle. While the studios supported themselves, the field photography was an expensive undertaking, especially on such a large and speculative scale. Brady's traveling battle photographers produced perhaps as many as 10,000 images, and some estimates put the cost of this at around $100,000 - $1,000 an image; the venture was entirely speculative, and Brady's hopes that the public or even the federal government would be interested in purchasing the images were crushed. Although his The Photographic History of the Civil War is considered a fascinating work today, the graphic nature of the images and a post-war depression lead to lukewarm sales in the period.

Debt continued to plague Brady, who had erroneously believed that the government would want to purchase his battlefield images. Even selling his New York studio could not stave off bankruptcy, and in 1875, when Congress voted to pay him $25,000 for his archive, he still remained in debt.

Brady's life ended sadly. Depressed by the death of his wife in 1887, frustrated by his continual struggle with debt, finding himself nearly blind as his eyes continued to deteriorate, and drinking heavily, he began to spiral downward. By 1896, Brady was an alcoholic, and following a streetcar accident, he died alone and penniless in New York's Presbyterian Hospital's charity ward on January 15, 1896. Upon news of his death, veterans of the 7th New York Infantry gathered enough funds to secure a proper burial, and Brady was interred in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

Brady's images are still popular today, perhaps because even in the period, they were of the finest quality and the highest standards in photography, and his staff photographers were equally talented. Many of the photographers associated with Brady's galleries (Alexander Gardner, Timothy O'Sullivan, etc.) went on to have prestigious careers in their own right. His images are also highly collectible because they capture some of the most iconic people and events of the mid-19th century: Lincoln's rise to prominence and his assassination, the Civil War, and the nearly-endless parade of famous people visiting the nation's capital. Today, Brady photographs command a range of prices from a few hundred dollars to thousands, depending on the subject matter, size, format, and, of course, condition.

Reference note by p4A.com Contributing Editor Robert M. Ginns and Senior Editor Hollie Davis, updated September 10, 2009.